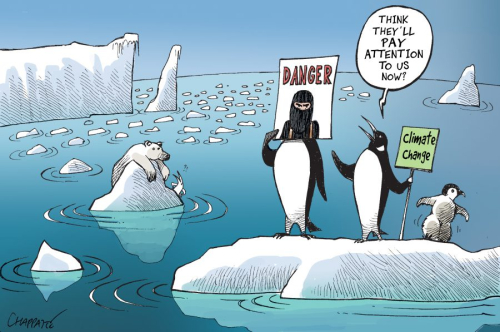

Today’s Dangers - 11 December 2015 - Chappatte

https://www.chappatte.com/en/gctheme/climate-change/

Article rédigé par Félix, Maximien Robin

Des mers et des océans fortement touchés

Le niveau des océans pourrait augmenter dangereusement à cause du réchauffement climatique. Le GIEC estime une élévation de 1 m en 2100. 3,8 milliards de personnes vivent sur les littoraux et sont exposés à des potentiels délocalisations, destructions d’habitats et d'infrastructures, et une augmentation des tempêtes côtières. Les submersions et les inondations détruisent les infrastructures portuaires et économiques, mais également les routes, ce qui immobilise un territoire. La fonte des glaces est également un facteur important dans la hausse des océans. Par exemple, la fonte de la calotte glaciaire de l’Arctique augmentera de 6 mètres les niveaux globales des mers, et de 65 mètres pour la fonte du glacier Thwaites en Antarctique. De plus, les océans deviennent de plus en plus acides. Ils absorbent plus ¼ des émissions en CO2. Les océans sont essentiels pour diminuer et ralentir le réchauffement climatique. Le CO2 est soluble dans l’H2O, cette eau riche en CO2 est plus dense et donc plonge vers le fond des océans. Les phytoplanctons absorbent le CO2 et le transforment en 02 à travers la photosynthèse. Mais, lorsque les eaux deviennent plus acides, elles absorbent moins de CO2 et donc aident à réchauffer l’atmosphère.

Des évènements climatiques extrêmes

On assiste déjà à une augmentation des événements extrêmes partout autour du globe ; tempêtes en Europe, sécheresses au Brésil, canicules en Russie et records de pluie au Bangladesh. De plus, ces événements sont de plus en plus longs et de plus en plus intenses. Un exemple de cette intensification est la canicule de 2003, qui a fait 15 000 morts en France, soit 55% de plus que prévu par le gouvernement. La fréquence de ces événements se fera principalement ressentir sur les inondations ; à l'horizon 2050, certaines villes deviendront des lieux d’inondations récurrents, comme la Nouvelle-Orléans, d'après les prévisions de précipitations accrues et l’augmentation du niveau de mer. Historiquement, cette augmentation se fait sentir, il y a eu 785 catastrophes naturelles entre 2001 et 2011 comparés à 407 entre 1980 et 1989, près de 2 fois plus en 30 ans. Les décès ont aussi fortement augmenté ; 600 000 sur la période 1987-1996 et 1,2 millions sur la période 1997-2007.

Une biodiversité menacée

Le réchauffement climatique met en danger l’abondance et la diversité des espèces mais aussi leur reproduction et alimentation. La biodiversité marine subit des changements non favorables comme : l'acidification, la désoxygénation et la hausse de température. En 2030, la majorité des récifs coralliens de l'océan indien et pacifiques seront menacés de disparition, la grande barrière de corail est déjà fortement blanchie (81% dans le secteur nord). Il y a également l’apparition des espèces invasives, qui devront quitter leur environnement natal à cause du réchauffement, et détruiront davantage l'écosystème, comme les scolytes en France. Le réchauffement climatique cause aussi la perturbation des cycles végétaux et animaux (floraison précoce, éclosion précoce et migration précoce) ce qui provoque une désynchronisation problématique pour les espèces indépendantes

Une insécurité alimentaire grandissante

L’insécurité alimentaire est la première cause de mort infantile dans les pays émergents. La malnutrition menace 13% de la population globale, dont 148 millions d’enfants. Ces chiffres vont diminuer avec le développement économique de l’Afrique mais ils pourraient être plus bas sans le réchauffement climatique : 138,5 millions en 2050 avec le réchauffement, contre 113 sans. L’augmentation exponentielle des températures va baisser les stocks de production agricole et donc l’offre alimentaire. De plus, les ministres de la défense sonnent l’alarme sur les éventuelles guerres du climat. A l'échelle nationale, les sécheresse, comme celle de Syrie entre 2007 et 2011 pourront aider à rompre les liens culturels nationaux. A l’échelle régionale, les dégradations des terres poussent aux populations à migrer et donc déstabiliser leurs pays voisins. La hausse du niveau des océans peut aussi amener à des migrations. Ensuite, la raréfaction de certaines ressources pousse différents acteurs à se confronter. Le réchauffement climatique pose également un défi sanitaire aux pays. L'humidité croissante est un environnement propice à l'apparition de moustiques, qui sont des vecteurs de maladies exotiques, comme la dengue. On assiste généralement à une recrudescence des maladies.

Des coûts financiers très importants

En 2006, l’économiste Nicholas Stern a publié une étude sur les coûts économique et monétaire du réchauffement climatique. Selon lui, les bénéfices d'une action rapide sont bien plus grands que le coût de l’inaction. Si rien n’est tenté, le coût sur 10 ans du réchauffement s’élèvera à 5,5 mille milliards d’euros chaque année. De plus, le service rendu par les écosystèmes est estimé à 29 mille milliards d’euros par an. Leur disparition sera destructrice pour l'économie du monde. Par exemple, la disparition des coraux coûtera 120 milliards d'euros par an. Les migrations internes dans les pays émergents vont déstabiliser leur économie et leur équilibre socio-culturel. De plus, L'empêchement de la recrudescence des virus a un coût considérable ; 2 à 4 milliards de dollars par an d’ici 2030